27th September 2016

Today the International Trade Secretary, Liam Fox, gave a speech about the WTO.

In this speech, he says:

The UK is a full and founding member of the WTO.

We have our own schedules that we currently share with the rest of the EU.

These set out our national commitments in the international trading system.

The UK will continue to uphold these commitments when we leave the European Union.

(There is a great fisking of this speech by Ian Dunt here.)

This speech follows the recent statement of the Chancellor of the Exchequer that EU funding will be guaranteed until 2020.

Could it be that the United Kingdom is not heading for a Hard Brexit or a Soft Brexit, but a Brexit existing as a name only?

Could there be a BEANO Brexit?

**

For email alerts for my posts at Jack of Kent, the FT and elsewhere, please submit your email address in the “Subscribe” box on this page.

Regular blogging at Jack of Kent is made possible by the kind sponsorship of Hammicks Legal Information Services.

Please click on this link to Hammicks and have a browse.

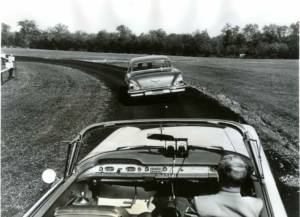

Twenty-one years ago, when we were shooting Triumph of the Nerds, the director, Paul Sen, introduced me to his cousin who was working at the time on a big Department of Transportation research program to build self-driving cars. Twenty-one years ago! Yet what goes around comes around and today there is nothing fresher than autonomous cars, artificial intelligence. You know, old stuff.

Twenty-one years ago, when we were shooting Triumph of the Nerds, the director, Paul Sen, introduced me to his cousin who was working at the time on a big Department of Transportation research program to build self-driving cars. Twenty-one years ago! Yet what goes around comes around and today there is nothing fresher than autonomous cars, artificial intelligence. You know, old stuff.

As you can see from this picture, driverless cars were tested by RCA and General Motors decades earlier, back in the 1950s.

What changed from 1995 until today in my view comes down to three major things: 1) 21 years of cumulative automotive research; 2) demographic changes that might — just might — make us a little more willing to give up our cars, and the big one; 3) Moore’s Law finally making possible cars that might be safe to drive themselves on city streets. But if this is, as it seems to be, the Summer of Love for autonomous vehicles. none of those are the real reason for all the recent action. The real reason is greed.

Back in 1995 the goals for self-driving cars were more modest than they are today. They weren’t called autonomous, but self-driving. And there was no plan to have cars drive themselves on city streets, just on freeways and highways — on the Interstate. The plan was to bury cables in the pavement over which all the cars would drive and communicate with each other and with the road, itself. The goal was to fill the road with cars driving at the speed limit, spaced precisely one meter apart. Ironically that simple system, which we could implement cheaply today, would achieve most of the economic and societal goals being pointed to today to support autonomous cars. We’re told they will be safer, make more efficient use of public roads, and use less energy. And it’s all true. Why, then, are we so eager to perform the much harder job of building truly autonomous cars that can pick the kids up at school? Greed again.

I really got into this concept back in 1995. Hand-driven cars filled at most 15 percent of the roadway while self-driving cars could fill 85 percent.That one-meter spacing was key, too: if there were only two cars headed south on the same remote stretch of Interstate the system would still put them one meter apart. That’s because a 70 mph rear-ender with only 39.37 inches to accelerate barely dents your bumper, designing completely out of the system more than half of all highway accidents.

Cars one meter apart draft each other just like NASCAR racers, reducing total aerodynamic drag and fuel consumption. And instead of each driver raggedly accelerating from a stop at his own rate and own sweet time, every car would start at exactly the same time and acceleration rate just like they are being driven by, well, a computer.

None of this sounds like the autonomous cars of today, though. Nobody is talking about a system where cars scream down the road at high speed and in such close proximity because the idea is scary and because the design philosophy of today’s self-driving cars is different. They are autonomous, which means they operate independently. They also aren’t supposed to scare us even if the scary part is actually the safer part.

Now we get to the greed. If most of the benefit could be obtained with cheaper self-driving cars, why do we now want autonomous cars? Because cars could be upgraded to self-driving through aftermarket upgrades, which is how they did it in 1995. Truly autonomous cars, though, you have to build those babies from scratch.

So everyone is going to need a new car.

Mandatory replacement is a glorious thing for manufacturers. It’s like that box of baking soda in the back of your refrigerator that you are supposed to throw away every 30 days. The golden era of the record business was when vinyl gave way to CDs and we all paid again to buy the same stuff we already owned. It happened again when we converted our VHS tape libraries to DVDs and to so some extent when we gave up physical media for iTunes.

It’s a glorious thing, the prospect of selling 200 million brand new cars and trucks over a 2-3 year period. And it’s coming, it’s absolutely coming.

Ford says it will have a self-driving taxi without a steering wheel in service by 2021. That’s a key data point because there’s no way Ford can afford the liability of putting those truly driverless cars on the road if they’ll be mixing it up with me in my 1994 Jeep Grand Cherokee that still smells faintly of mice.

For autonomous cars to be successful they will have to totally dominate, which will require new laws, getting old cars off the roads. This is the part they couldn’t do back in 1995. The banks will have to lend lots of money (with federal guarantees, I’m sure), old cars like mine will have to be melted down. It will be a huge endeavor that will also involve a serious increase in electric vehicles.

And it will happen. Shit, we all know there’s a recession coming after the election, followed by Japanese-style deflation unless we can find a way to really juice the economy. George W. Bush used a housing bubble for that after 9/11 but those tricks have been all used-up. And there’s no more room for the Fed to drop interest rates.

So autonomous cars it must be.

Appealing to both sides of the aisle, car factories will soon be running three shifts, infrastructure will be rebuilt at the same time, and even global warming will be quietly addressed if not accepted on the right — all while saving lives and increasing elderly mobility.

Heck of a deal. I’ll just whistle for my car like Roy Rogers summoning Trigger.

But will I have to also give up my Bugeye Sprite? Probably, unless Sundays are made non-autonomous car days.

I’m not saying this is entirely a bad thing or even mainly a bad thing. It’s just a thing we’ll have to deal with. And I thought it was only fair to tell you it’s coming.

Digital Branding

Web Design Marketing

Woo hoo! Microsoft has announced that SQL Server 2016 will be generally available on June 1st. On that date all four versions of SQL Server 2016 will be available to all users, including brand new ones, MSDN subscribers, and existing customers.

Here is a quick overview of the tons of new features, broken out by edition (click for larger view):

and here is another view on the features available for each edition (click for larger view):

In addition to the on-premises release, Microsoft will also have a virtual machine available on June 1st through its Azure cloud platform to make it real easy for companies to deploy SQL Server 2016 in the cloud. So start planning today!

More info:

Get ready, SQL Server 2016 coming on June 1st

Microsoft SQL Server 2016 will be generally available June 1

This chart is for the UK though the graph for the whole of the developed countries looks similar. If updated for the most recent times it would be gradually trending up by now, but not in any danger of returning to anywhere near the pre-crisis trendline.

The developed world is moving towards its eighth year of constant under-performance, though in both the US and the UK, a sufficient part of the hit has been in the form of lower than otherwise income growth (except for those at the top) enabling unemployment to fall to tolerably low levels. But everywhere the hit to income has been huge. And growth remains sluggish with governments committed not to expanding budgets but to repairing them and to repairing their legacy – government debt. Meanwhile monetary policy sits with overnight cash rates with central banks at or near zero. (Note, this post is not about Australia’s situation because our interest rates are positive. To avoid zero interest rates official macro-economic policy makers are pursuing a doctrine that targets higher unemployment. As I observed here, it’s a new idea that this could be the best we can do. Of course it could be. But call me old fashioned, but I thought that was to be demonstrated – you know with coherent economic models and that kind of thing – but then I’m not even invited into the Qantas Captain’s Club, so what would I know?).

Meanwhile central banks havetried one innovation - quantitative easing (QE). The hard money cranksthink it’s a terrible idea. But plenty of thoughtful people are worried too. This argument is often put by people who think that – as Lady Bracknell said of statistics – markets are sent for our guidance. It’s hard not to see it as a theory that financial markets don’t really work. Ironically the ‘left’ Keynesian Hyman Minsky argued that too much prosperity eventually undermined itself as it fed the gradual infection of the market with speculation and more and more elaborate financial engineering and deception – what J.K. Galbraith referred to as the ‘bezzle‘. Meanwhile many scolds of keeping cash rates low argue that toolittle prosperity – too depressed a money market – leads to the same thing via the search for yield. Each seems to be arguing that private financial markets are pretty unstable things that are ill-adapted to promoting the common good.

Even without this, QE does seem to have some nasty bugs. It’s inefficient. If investment is being held down by depressed ‘animal spirits’ then lowering interest rates – including longer term interest rates which is what QE targets – can only address that very indirectly. Investment is usually depressed in recessions and depressions because of a lack of demand for final outputs – addressing that would be the direct way to get investment returning to a more normal share of economic activity. Meanwhile QE is funded by central banks creating money with which they support the price of assets owned by wealthy people and if the central bank is successful, one presumes it sells back the assets at lower prices – as growth resumes, interest rates return to more ‘normal’ higher levels and so the price of the assets falls. The public has used the money it’s manufactured to buy high and sell low! (This wouldn’t follow if QE involved buying shares which might well rise in such circumstances, but QE has hitherto involved the central bank purchase of high quality income bearing assets.) So QE unfair and inefficient – exactly the opposite of what we’re after here at Club Troppo.

The alternative is ‘helicopter money’ in which the central bank manufactures money – as it does with QE – but lavishes it on the ‘real’ not the financial economy. It could do it directly itself – sending out cheques (or in Milton Friedman’s original example dropping notes from a helicopter) – or more usually via the government – by funding some government outlay or a tax holiday. It’s always seemed to me that QE has been restricted to asset markets for the essentially arbitrary reason that it makes more sense given the historical development of central banking rather than because that restriction makes economic sense. The central bank is seeking to inject money into the system which state of affairs it believes will be temporary. But doing it through asset purchases is sufficiently indirect a way to act on the economy that the ‘temporary’ nature of QE could last an awfully long time (as we are discovering). Money created and directly spent in the economy seems much more likely to get things going.

Still if that’s the case, there’s a bug as I explained elsewhere:

In normal times it seems that ‘traditional’ ways of thinking of budget deficits might operate quite neatly to encapsulate the constraints on governments trying to optimise economic management. So printing more money might get you out of a recession, but then, once a recovery gets underway, you’ve got a lot of extra money sloshing around which you need to withdraw from the system – which you’d do by taxing more and/or reducing government spending. But that’s what you’d have to do if you’d debt financed your way out of a recession – loosening fiscal policy (borrowing to run a deficit) and then tightening fiscal policy (running a surplus and repaying some or all of the debt) after the event.

This perhaps explains why those proposing helicopter money seem to have been so tentative. One such has been former head of the Financial Services Authority, Adair Turner, Baron of Ecchinswell (why he was rejected for a knighthood by our former Prime Minister we can never know). Anyway, on the eve of his departure from the FSA Turner gave a lengthy speech which finally worked up the courage to say that maybe, in some circumstances, though not in these circumstances, we should entertain the idea of seriously considering money finance – sometimes called helicopter money. I haven’t looked it up but it was something of a cause célèbre at the time. Since then, unburdened by the position (though presumably with the interests of the kind people of Ecchinswell remaining firmly in his mind) and as a faculty member and now Chair of the governing board of George Soros’s (IAEIPNET) Institute for Already Extremely Important People engaging in New Economic Thinking he has written a book and plenty of columns on the idea.

He’s a smart guy whose writing I appreciate because he seems to wrestle with perhaps not knowing his subject as well as the best academics (it’s such an immense, technical and conceptually tricky area), but nevertheless has the courage to make proposals and risk making a fool of himself – not unlike your humble correspondent here at Troppo. However, though I’ve not read his book, I have read quite a few of the columns and the reticence remains. He concluded in a recent columnthat:

amid the confusion, the one really important political issue is ignored: whether we can design rules and allocate institutional responsibilities to ensure that monetary financing is used only in an appropriately moderate and disciplined fashion, or whether the temptation to use it to excess will prove irresistible.

As I’ve already half done the job, I’ll address the task Baron Turner has set in part two.

To be continued …